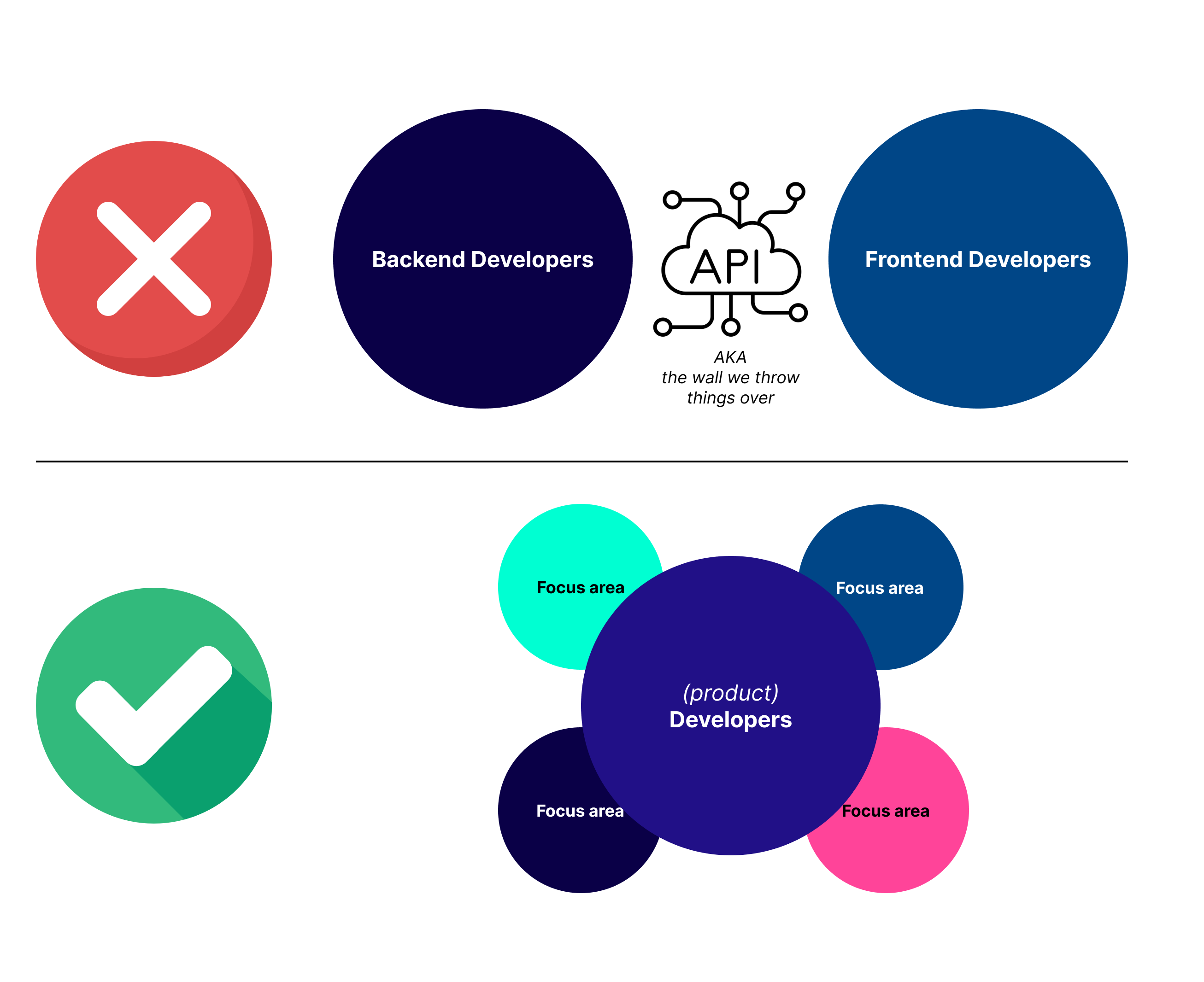

I am fairly convinced that for many of us who create software products, putting the words "backend" or "frontend" into the titles of our developers can be a pretty damaging thing to do to our organizations, and via Conway's law, to our software products.

Doing so inevitably creates backend/frontend teams, backend/frontend chapters, backend/frontend channels in our communication tools, and the list goes on and on. Silos emerge, people are blocked, and our products suffer as individuals make technical decisions which often prioritize not having to deal with “the other people's stuff” rather than the best solution for the product.

At the end of the day, we’re all working towards the same goal and the ownership of that can be shared. Instead, organizations often end up asking questions like:

- How many backend developers should we hire per frontend developer?

- (During Sprint planning): is there enough frontend/backend work in this sprint to match our capacities? (Note the plural here)

- Who can fix [extremely minor frontend issue] now that [frontend dev] is on vacation?

I am not arguing that everyone should be masters of everything. People should still be able to specialize in the focus areas they want to engage in. But I think it’s important to assess whether problems like the above arise as self-made problems by an organization which tells their developers that they’re supposed to be backend or frontend (only) developers - especially when the reality can be much more fluid and dynamic than that.

There exist no developers who - given the right culture - can’t obtain the technical ability to change the color of a button or rename an API endpoint with relative ease, unless our organizations create and enforce boundaries that disallow this. Developers in turn internalize such boundaries and believe them to be identifiers of their position and responsibilities, and the divide grows over time.

These days it’s easier than ever to bridge the technical part of this divide. Full-stack solutions like tRPC or openAPI/Swagger-generated types can be great enablers of reducing the divide between layers of architecture. You can utilize these tools to pull a so-called inverse Conway maneuver; letting the technology influence the design of the organization, rather than the other way around.

Of course there are exceptions to the above; if you’re working with microservices or building an API which gets consumed by many different external clients, and you've designed your team around something like the x-as-a-service model, you're probaly good to go. In fact, so long as you're actively evaluating whether a given structure works for your organization, you are probably going to be fine in the long run.

But I have seen many organizations that build one product, consisting of one API, which is consumed by one client, who still divide their architecture, people and culture along the lines of "frontend" and "backend". Not because of an active decision, but because it’s the way we’re used to.

The result is inefficient - and if you ask me - uninspiring to partake in.

On the other hand, I've now worked in a few organizations which came to a point of actively deciding to break down these barriers, including stripping the words "frontend" and "backend" from the titles of developers, leaving us with... just developers doing development. And the results have been amazing. Questions like the ones listed above seem to vanish, and the vast majority of developers start growing in all kinds of interesting ways as they realize that they themselves can eliminate bottlenecks that used to hold them back.

It takes work though - it's paramount that your developers get the support they need to bridge the gap, and that such a change is done with them, not to them. But if you succeed, you will see benefits for both the engineering department and the larger organization in places you weren't even expecting.

And more importantly - to me as a developer anyway - it's way more fun. Or as one of my fellow developers put it during one such transition:

"I've spent the last few months working on things I didn't feel good enough at to be doing. And... I don't know, it just keeps on working."